Molecular Biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that deals with the molecular basis of biological activity. This field overlaps with other areas of biology and chemistry, particularly genetics and biochemistry. Molecular biology chiefly concerns itself with understanding the interactions between the various systems of a cell, including the interactions between the different types of DNA, RNA and protein biosynthesis as well as learning how these interactions are regulated.

Writing in Nature in 1961, William Astbury described molecular biology as-

"...not so much a technique as an approach, an approach from the viewpoint of the so-called basic sciences with the leading idea of searching below the large-scale manifestations of classical biology for the corresponding molecular plan. It is concerned particularly with the forms of biological molecules and [...] is predominantly three-dimensional and structural—which does not mean, however, that it is merely a refinement of morphology. It must at the same time inquire into genesis and function."

Writing in Nature in 1961, William Astbury described molecular biology as-

"...not so much a technique as an approach, an approach from the viewpoint of the so-called basic sciences with the leading idea of searching below the large-scale manifestations of classical biology for the corresponding molecular plan. It is concerned particularly with the forms of biological molecules and [...] is predominantly three-dimensional and structural—which does not mean, however, that it is merely a refinement of morphology. It must at the same time inquire into genesis and function."

|

|

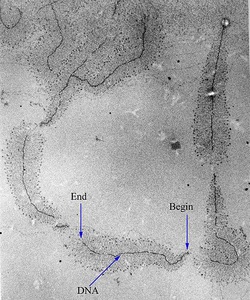

DNA Replication

DNA replication is a biological process that occurs in all living organisms and copies their DNA; it is the basis for biological inheritance. The process starts when one double-stranded DNA molecule produces two identical copies of the molecule. The cell cycle (mitosis) also pertains to the DNA replication/reproduction process. The cell cycle includes interphase, prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Each strand of the original double-stranded DNA molecule serves as template for the production of the complementary strand, a process referred to as semiconservative replication. Cellular proofreading and error toe-checking mechanisms ensure near perfect fidelity for DNA replication.[1][2]

In a cell, DNA replication begins at specific locations in the genome, called "origins".[3] Unwinding of DNA at the origin, and synthesis of new strands, forms a replication fork. In addition to DNA polymerase, the enzyme that synthesizes the new DNA by adding nucleotides matched to the template strand, a number of other proteins are associated with the fork and assist in the initiation and continuation of DNA synthesis. DNA replication can also be performed in vitro (artificially, outside a cell). DNA polymerases, isolated from cells, and artificial DNA primers are used to initiate DNA synthesis at known sequences in a template molecule. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a common laboratory technique, employs such artificial synthesis in a cyclic manner to amplify a specific target DNA fragment from a pool of DNA. The replication fork is a structure that forms within the nucleus during DNA replication. It is created by helicases, which break the hydrogen bonds holding the two DNA strands together. The resulting structure has two branching "prongs", each one made up of a single strand of DNA. These two strands serve as the template for the leading and lagging strands, which will be created as DNA polymerase matches complementary nucleotides to the templates; The templates may be properly referred to as the leading strand template and the lagging strand templates Leading strand The leading strand is the template strand of the DNA double helix so that the replication fork moves along it in the 3' to 5' direction. This allows the newly synthesized strand complementary to the original strand to be synthesized 5' to 3' in the same direction as the movement of the replication fork. On the leading strand, a polymerase "reads" the DNA and adds nucleotides to it continuously. This polymerase is DNA polymerase III (DNA Pol III) in prokaryotes and presumably Pol ε[7][12] in yeasts. In human cells the leading and lagging strands are synthesized by Pol α and Pol δ within the nucleus and Pol γ in the mitochondria. Pol ε can substitute for Pol δ in special circumstances.[13] Lagging strand The lagging strand is the strand of the template DNA double helix that is oriented so that the replication fork moves along it in a 5' to 3' manner. Because of its orientation, opposite to the working orientation of DNA polymerase III, which moves on a template in a 3' to 5' manner, replication of the lagging strand is more complicated than that of the leading strand. On the lagging strand, primase "reads" the DNA and adds RNA to it in short, separated segments. In eukaryotes, primase is intrinsic to Pol α.[14] DNA polymerase III or Pol δ lengthens the primed segments, forming Okazaki fragments. Primer removal in eukaryotes is also performed by Pol δ.[15] In prokaryotes, DNA polymerase I "reads" the fragments, removes the RNA using its flap endonuclease domain (RNA primers are removed by 5'-3' exonuclease activity of polymerase I [weaver, 2005], and replaces the RNA nucleotides with DNA nucleotides (this is necessary because RNA and DNA use slightly different kinds of nucleotides). DNA ligase joins the fragments together. |

Transcription Processes

Transcription is the process of creating a complementary RNA copy of a sequence of DNA.[1] Both RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a complementary language that can be converted back and forth from DNA to RNA by the action of the correct enzymes. During transcription, a DNA sequence is read by an RNA polymerase, which produces a complementary, antiparallel RNA strand. As opposed to DNA replication, transcription results in an RNA complement that includes uracil (U) in all instances where thymine (T) would have occurred in a DNA complement. Also unlike DNA replication where DNA is synthesised, transcription does not involve an RNA primer to initiate RNA synthesis.

Transcription is explained easily in 4 or 5 steps, each moving like a wave along the DNA.

A DNA transcription unit encoding for a protein contains not only the sequence that will eventually be directly translated into the protein (the coding sequence) but also regulatory sequences that direct and regulate the synthesis of that protein. The regulatory sequence before (upstream from) the coding sequence is called the five prime untranslated region (5'UTR), and the sequence following (downstream from) the coding sequence is called the three prime untranslated region (3'UTR).[2] Transcription has some proofreading mechanisms, but they are fewer and less effective than the controls for copying DNA; therefore, transcription has a lower copying fidelity than DNA replication.[3] As in DNA replication, DNA is read from 3' → 5' during transcription. Meanwhile, the complementary RNA is created from the 5' → 3' direction. This means its 5' end is created first in base pairing. Although DNA is arranged as two antiparallel strands in a double helix, only one of the two DNA strands, called the template strand, is used for transcription. This is because RNA is only single-stranded, as opposed to double-stranded DNA. The other DNA strand is called the coding (lagging) strand, because its sequence is the same as the newly created RNA transcript (except for the substitution of uracil for thymine). The use of only the 3' → 5' strand eliminates the need for the Okazaki fragments seen in DNA replication.[2] Transcription is divided into 5 stages: pre-initiation, initiation, promoter clearance, elongation and termination. |

|

|

|

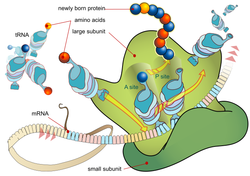

Protein Synthesis

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the third stage of protein biosynthesis (part of the overall process of gene expression). In translation, messenger RNA (mRNA) produced by transcription is decoded by the ribosome to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide, that will later fold into an active protein. In Bacteria, translation occurs in the cell's cytoplasm, where the large and small subunits of the ribosome are located, and bind to the mRNA. In Eukaryotes, translation occurs across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum in a process called vectorial synthesis. The ribosome facilitates decoding by inducing the binding of tRNAs with complementary anticodon sequences to that of the mRNA. The tRNAs carry specific amino acids that are chained together into a polypeptide as the mRNA passes through and is "read" by the ribosome in a fashion reminiscent to that of a stock ticker and ticker tape.

In many instances, the entire ribosome/mRNA complex causing it to bind to the outer membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and release the nascent protein polypeptide inside for later vesicle transport and secretion outside of the cell. Many types of transcribed RNA, such as transfer RNA, ribosomal RNA, and small nuclear RNA, do not undergo translation into proteins. Translation proceeds in four phases: initiation, elongation, translocation and termination (all describing the growth of the amino acid chain, or polypeptide that is the product of translation). Amino acids are brought to ribosomes and assembled into proteins. In activation, the correct amino acid is covalently bonded to the correct transfer RNA (tRNA). The amino acid is joined by its carboxyl group to the 3' OH of the tRNA by an ester bond. When the tRNA has an amino acid linked to it, it is termed "charged". Initiation involves the small subunit of the ribosome binding to the 5' end of mRNA with the help of initiation factors (IF). Termination of the polypeptide happens when the A site of the ribosome faces a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA). No tRNA can recognize or bind to this codon. Instead, the stop codon induces the binding of a release factor protein that prompts the disassembly of the entire ribosome/mRNA complex. A number of antibiotics act by inhibiting translation; these include anisomycin, cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, erythromycin, and puromycin, among others. Prokaryotic ribosomes have a different structure from that of eukaryotic ribosomes, and thus antibiotics can specifically target bacterial infections without any detriment to a eukaryotic host's cells. |

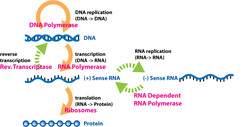

Central Dogma Of Biology

The central dogma of molecular biology describes the way genetic information is expected to be transferred in a single direction through a biological system. It was first stated by Francis Crick in 1958[1] and re-stated in a Nature paper published in 1970:[2]

The central dogma of molecular biology deals with the detailed residue-by-residue transfer of sequential information. It states that such information cannot be transferred back from protein to either protein or nucleic acid. Or, as Marshall Nirenberg said, "DNA makes RNA makes protein."[3] The dogma is a framework for understanding the transfer of sequence information between sequential information-carrying biopolymers, in the most common or general case, in living organisms. There are 3 major classes of such biopolymers: DNA and RNA (both nucleic acids), and protein. There are 3×3 = 9 conceivable direct transfers of information that can occur between these. The dogma classes these into 3 groups of 3: 3 general transfers (believed to occur normally in most cells), 3 special transfers (known to occur, but only under specific conditions in case of some viruses or in a laboratory), and 3 unknown transfers (believed never to occur). The general transfers describe the normal flow of biological information: DNA can be copied to DNA (DNA replication), DNA information can be copied into mRNA (transcription), and proteins can be synthesized using the information in mRNA as a template (translation). |

|

|

|

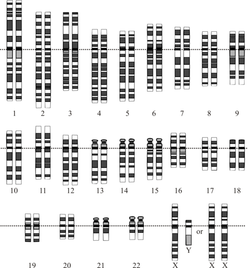

What is Our Genome?

The human (Homo sapiens) genome is the complete set of human genetic information, stored as DNA sequences within the 23 chromosome pairs of the cell nucleus, and in a small DNA molecule within the mitochondrion. The haploid human genome (as represented in egg and sperm cells) consists of just over three billion DNA base pairs, while the diploid genome (as represented in somatic cells) has twice the DNA content.

The Human Genome Project produced the first complete sequences of individual human genomes. As of 2012, thousands of human genomes have been completely sequenced, and many more have been mapped at lower levels of resolution. The resulting data are used worldwide in biomedical science, anthropology, and other branches of science. There is a widely-held expectation that genomic studies will lead to advances in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, and to new insights in many fields of biology, including human evolution. The haploid human genome contains roughly 20,000 protein-coding genes, far fewer than had been anticipated.[1][2] About 1.5% of the genome encodes proteins, while the rest is associated with non-coding RNA molecules, regulatory DNA sequences, introns, and sequences to which no function has yet been assigned.[ |

DNA Technologies

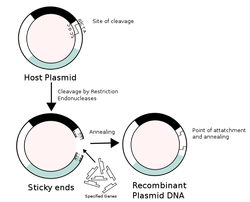

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods (molecular cloning) to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms. Recombinant DNA is possible because DNA molecules from all organisms share the same chemical structure; they differ only in the sequence of nucleotides within that identical overall structure. Consequently, when DNA from a foreign source is linked to host sequences that can drive DNA replication and then introduced into a host organism, the foreign DNA is replicated along with the host DNA.

Recombinant DNA molecules are sometimes called chimeric DNA, because they are usually made of material from two different species, like the mythical chimera. R-DNA technology uses palindromic sequences and leads to the production of sticky and blunt ends. The DNA sequences used in the construction of recombinant DNA molecules can originate from any species. For example, plant DNA may be joined to bacterial DNA, or human DNA may be joined with fungal DNA. In addition, DNA sequences that do not occur anywhere in nature may be created by the chemical synthesis of DNA, and incorporated into recombinant molecules. Using recombinant DNA technology and synthetic DNA, literally any DNA sequence may be created and introduced into any of a very wide range of living organisms. Proteins that result from the expression of recombinant DNA within living cells are termed recombinant proteins. When recombinant DNA encoding a protein is introduced into a host organism, the recombinant protein will not necessarily be produced.[citation needed] Expression of foreign proteins requires the use of specialized expression vectors and often necessitates significant restructuring of the foreign coding sequence.[citation needed] Recombinant DNA differs from genetic recombination in that the former results from artificial methods in the test tube, while the latter is a normal biological process that results in the remixing of existing DNA sequences in essentially all organisms. Molecular cloning is the laboratory process used to create recombinant DNA.[1][2][3][4] It is one of two widely-used methods (along with polymerase chain reaction, abbr. PCR) used to direct the replication of any specific DNA sequence chosen by the experimentalist. The fundamental difference between the two methods is that molecular cloning involves replication of the DNA within a living cell, while PCR replicates DNA in the test tube, free of living cells. Formation of recombinant DNA requires a cloning vector, a DNA molecule that will replicate within a living cell. Vectors are generally derived from plasmids or viruses, and represent relatively small segments of DNA that contain necessary genetic signals for replication, as well as additional elements for convenience in inserting foreign DNA, identifying cells that contain recombinant DNA, and, where appropriate, expressing the foreign DNA. The choice of vector for molecular cloning depends on the choice of host organism, the size of the DNA to be cloned, and whether and how the foreign DNA is to be expressed.[5] The DNA segments can be combined by using a variety of methods, such as restriction enzyme/ligase cloning or Gibson assembly. In standard cloning protocols, the cloning of any DNA fragment essentially involves seven steps: (1) Choice of host organism and cloning vector, (2) Preparation of vector DNA, (3) Preparation of DNA to be cloned, (4) Creation of recombinant DNA, (5) Introduction of recombinant DNA into the host organism, (6) Selection of organisms containing recombinant DNA, (7) Screening for clones with desired DNA inserts and biological properties.[4] These steps are described in some detail in a related article (molecular cloning). |

|