Cell Biology

Cell biology (formerly cytology, from the Greek kytos, "contain") is a scientific discipline that studies cells – their physiological properties, their structure, the organelles they contain, interactions with their environment, their life cycle, division and death. This is done both on a microscopic and molecular level. Cell biology research encompasses both the great diversity of single-celled organisms like bacteria and protozoa, as well as the many specialized cells in multicellular organisms such as humans.

Knowing the components of cells and how cells work is fundamental to all biological sciences. Appreciating the similarities and differences between cell types is particularly important to the fields of cell and molecular biology as well as to biomedical fields such as cancer research and developmental biology. These fundamental similarities and differences provide a unifying theme, sometimes allowing the principles learned from studying one cell type to be extrapolated and generalized to other cell types. Therefore, research in cell biology is closely related to genetics, biochemistry, molecular biology, immunology, and developmental biology.

Knowing the components of cells and how cells work is fundamental to all biological sciences. Appreciating the similarities and differences between cell types is particularly important to the fields of cell and molecular biology as well as to biomedical fields such as cancer research and developmental biology. These fundamental similarities and differences provide a unifying theme, sometimes allowing the principles learned from studying one cell type to be extrapolated and generalized to other cell types. Therefore, research in cell biology is closely related to genetics, biochemistry, molecular biology, immunology, and developmental biology.

|

|

Overview Of A Cell

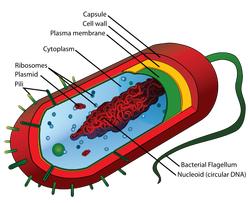

Prokaryotic cells Main article: Prokaryote Diagram of a typical prokaryotic cell The prokaryote cell is simpler, and therefore smaller, than a eukaryote cell, lacking a nucleus and most of the other organelles of eukaryotes. There are two kinds of prokaryotes: bacteria and archaea; these share a similar structure.

The nuclear material of a prokaryotic cell consists of a single chromosome that is in direct contact with the cytoplasm. Here, the undefined nuclear region in the cytoplasm is called the nucleoid. A prokaryotic cell has three architectural regions:

|

Tour Of An Eukaryotic Cell

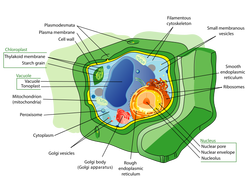

Eukaryotic cells Main article: Eukaryote Plants, animals, fungi, slime moulds, protozoa, and algae are all eukaryotic. These cells are about 15 times wider than a typical prokaryote and can be as much as 1000 times greater in volume. The major difference between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is that eukaryotic cells contain membrane-bound compartments in which specific metabolic activities take place. Most important among these is a cell nucleus, a membrane-delineated compartment that houses the eukaryotic cell's DNA. This nucleus gives the eukaryote its name, which means "true nucleus." Other differences include:

Parts Of Eukaryotic Cell

Subcellular components All cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic, have a membrane that envelops the cell, separates its interior from its environment, regulates what moves in and out (selectively permeable), and maintains the electric potential of the cell. Inside the membrane, a salty cytoplasm takes up most of the cell volume. All cells possess DNA, the hereditary material of genes, and RNA, containing the information necessary to build various proteins such as enzymes, the cell's primary machinery. There are also other kinds of biomolecules in cells. This article lists these primary components of the cell, then briefly describe their function.

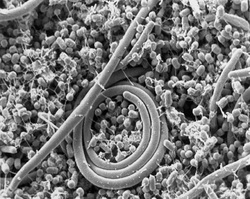

Membrane : Cell membrane The cytoplasm of a cell is surrounded by a cell membrane or plasma membrane. The plasma membrane in plants and prokaryotes is usually covered by a cell wall. This membrane serves to separate and protect a cell from its surrounding environment and is made mostly from a double layer of lipids (hydrophobic fat-like molecules) and hydrophilic phosphorus molecules. Hence, the layer is called a phospholipid bilayer. It may also be called a fluid mosaic membrane. Embedded within this membrane is a variety of protein molecules that act as channels and pumps that move different molecules into and out of the cell. The membrane is said to be 'semi-permeable', in that it can either let a substance (molecule or ion) pass through freely, pass through to a limited extent or not pass through at all. Cell surface membranes also contain receptor proteins that allow cells to detect external signaling molecules such as hormones. Cytoskeleton : Cytoskeleton Bovine Pulmonary Artery Endothelial cell: nuclei stained blue, mitochondria stained red, and F-actin, an important component in microfilaments, stained green. Cell imaged on a fluorescent microscope. The cytoskeleton acts to organize and maintain the cell's shape; anchors organelles in place; helps during endocytosis, the uptake of external materials by a cell, and cytokinesis, the separation of daughter cells after cell division; and moves parts of the cell in processes of growth and mobility. The eukaryotic cytoskeleton is composed of microfilaments, intermediate filaments and microtubules. There is a great number of proteins associated with them, each controlling a cell's structure by directing, bundling, and aligning filaments. The prokaryotic cytoskeleton is less well-studied but is involved in the maintenance of cell shape, polarity and cytokinesis.[7] Genetic material Two different kinds of genetic material exist: deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). Most organisms use DNA for their long-term information storage, but some viruses (e.g., retroviruses) have RNA as their genetic material. The biological information contained in an organism is encoded in its DNA or RNA sequence. RNA is also used for information transport (e.g., mRNA) and enzymatic functions (e.g., ribosomal RNA) in organisms that use DNA for the genetic code itself. Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules are used to add amino acids during protein translation. Prokaryotic genetic material is organized in a simple circular DNA molecule (the bacterial chromosome) in the nucleoid region of the cytoplasm. Eukaryotic genetic material is divided into different, linear molecules called chromosomes inside a discrete nucleus, usually with additional genetic material in some organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts (see endosymbiotic theory). A human cell has genetic material contained in the cell nucleus (the nuclear genome) and in the mitochondria (the mitochondrial genome). In humans the nuclear genome is divided into 23 pairs of linear DNA molecules called chromosomes. The mitochondrial genome is a circular DNA molecule distinct from the nuclear DNA. Although the mitochondrial DNA is very small compared to nuclear chromosomes, it codes for 13 proteins involved in mitochondrial energy production and specific tRNAs. Foreign genetic material (most commonly DNA) can also be artificially introduced into the cell by a process called transfection. This can be transient, if the DNA is not inserted into the cell's genome, or stable, if it is. Certain viruses also insert their genetic material into the genome. Organelles Main article: Organelle The human body contains many different organs, such as the heart, lung, and kidney, with each organ performing a different function. Cells also have a set of "little organs," called organelles, that are adapted and/or specialized for carrying out one or more vital functions. Both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells have organelles but organelles in eukaryotes are generally more complex and may be membrane bound. There are several types of organelles in a cell. Some (such as the nucleus and golgi apparatus) are typically solitary, while others (such as mitochondria, peroxisomes and lysosomes) can be numerous (hundreds to thousands). The cytosol is the gelatinous fluid that fills the cell and surrounds the organelles.

|

|

|

|

Membrane Transport Systems

In cellular biology the term membrane transport refers to the collection of mechanisms that regulate the passage of solutes such as ions and small molecules through biological membranes nain proteins embedded in them. The regulation of passage through the membrane is due to selective membrane permeability - a characteristic of biological membranes which allows them to separate substances of distinct chemical nature. In other words, they can be permeable to certain substances but not to others.[1]

The movements of most solutes through the membrane are mediated by membrane transport proteins which are specialized to varying degrees in the transport of specific molecules. As the diversity and physiology of the distinct cells is highly related to their capacities to attract different external elements, it is postulated that there is a group of specific transport proteins for each cell type and for every specific physiological stage[1]. This differential expression is regulated through the differential transcription of the genes coding for these proteins and its translation, for instance, through genetic-molecular mechanisms, but also at the cell biology level: the production of these proteins can be activated by cellular signaling pathways, at the biochemical level, or even by being situated in cytoplasmic vesicles. |

Microtubule Dynamics In A Cell

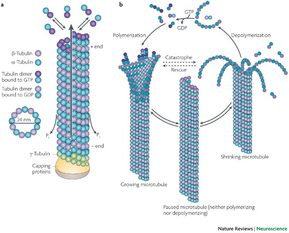

Microtubules are a component of the cytoskeleton. These cylindrical polymers of tubulin can grow as long as 25 micrometers and are highly dynamic. The outer diameter of microtubule is about 25 nm. Microtubules are important for maintaining cell structure, providing platforms for intracellular transport, forming the mitotic spindle, as well as other cellular processes.[1] There are many proteins that bind to microtubules, including motor proteins such as kinesin and dynein, severing proteins like katanin, and other proteins important for regulating microtubule dynamics.

Microtubules are long, hollow cylinders made up of polymerised α- and β-tubulin dimers. Tubulin dimers polymerize end to end in protofilaments which are the building block for the microtubule structure. Thirteen protofilaments associate laterally to form a single microtubule and this structure can then extend by addition of more protofilaments. The lateral association of the protofilaments generates an imperfect helix with one turn of the helix containing 13 tubulin dimers, each from a different protofilament. The image above illustrates a small section of microtubule, a few αβ dimers in length. The number of protofilaments can vary; microtubules made up of 14 protofilaments have been seen in vitro. Microtubules have a distinct polarity which is important for their biological function. Tubulin polymerizes end to end with the α subunit of one tubulin dimer contacting the β subunit of the next. Therefore, in a protofilament, one end will have the α subunit exposed while the other end will have the β subunit exposed. These ends are designated the (−) and (+) ends, respectively. The protofilaments bundle parallel to one another, so, in a microtubule, there is one end, the (+) end, with only β subunits exposed, while the other end, the (−) end, has only α subunits exposed. Elongation of microtubules typically only occurs from the (+) end. |

|

|

|

Cell Cell Communication Ideas

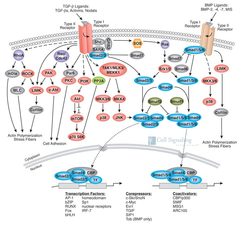

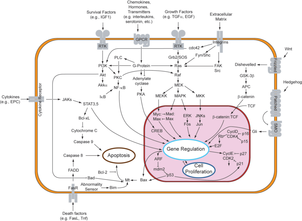

Cell signaling is part of a complex system communication that governs basic cellular activities and coordinates cell actions. The ability of cells to perceive and correctly respond to their microenvironment is the basis of development, tissue repair, and immunity as well as normal tissue homeostasis. Errors in cellular information processing are responsible for diseases such as cancer, autoimmunity, and diabetes. By understanding cell signaling, diseases may be treated effectively and, theoretically, artificial tissues may be created.[citation needed]

Traditional work in biology has focused on studying individual parts of cell signaling pathways. Systems biology research helps us to understand the underlying structure of cell signaling networks and how changes in these networks may affect the transmission and flow of information. Such networks are complex systems in their organization and may exhibit a number of emergent properties including bistability and ultrasensitivity. Analysis of cell signaling networks requires a combination of experimental and theoretical approaches including the development and analysis of simulations and modeling.[citation needed] Long-range allostery is often a significant component of cell signaling events. |

|

|

Cellular Signaling Pathways

Cells communicate with each other via direct contact (juxtacrine signaling), over short distances (paracrine signaling), or over large distances and/or scales (endocrine signaling).

Some cell-to-cell communication requires direct cell–cell contact. Some cells can form gap junctions that connect their cytoplasm to the cytoplasm of adjacent cells. In cardiac muscle, gap junctions between adjacent cells allows for action potential propagation from the cardiac pacemaker region of the heart to spread and coordinately cause contraction of the heart. The Notch signaling mechanism is an example of juxtacrine signaling (also known as contact-dependent signaling) in which two adjacent cells must make physical contact in order to communicate. This requirement for direct contact allows for very precise control of cell differentiation during embryonic development. In the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, two cells of the developing gonad each have an equal chance of terminally differentiating or becoming a uterine precursor cell that continues to divide. The choice of which cell continues to divide is controlled by competition of cell surface signals. One cell will happen to produce more of a cell surface protein that activates the Notch receptor on the adjacent cell. This activates a feedback loop or system that reduces Notch expression in the cell that will differentiate and that increases Notch on the surface of the cell that continues as a stem cell.[5] Many cell signals are carried by molecules that are released by one cell and move to make contact with another cell. Endocrine signals are called hormones. Hormones are produced by endocrine cells and they travel through the blood to reach all parts of the body. Specificity of signaling can be controlled if only some cells can respond to a particular hormone. Paracrine signals such as retinoic acid target only cells in the vicinity of the emitting cell.[6] Neurotransmitters represent another example of a paracrine signal. Some signaling molecules can function as both a hormone and a neurotransmitter. For example, epinephrine and norepinephrine can function as hormones when released from the adrenal gland and are transported to the heart by way of the blood stream. Norepinephrine can also be produced by neurons to function as a neurotransmitter within the brain.[7] Estrogen can be released by the ovary and function as a hormone or act locally via paracrine or autocrine signaling.[8] Active species of oxygen and nitric oxide can also act as cellular messengers. This process is dubbed redox signaling. |

Cell Division And It's Regulation

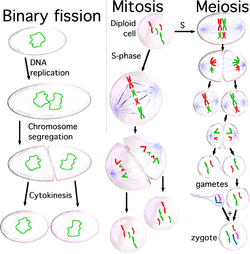

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells.[1] Cell division is usually a small segment of a larger cell cycle. This type of cell division in eukaryotes is known as mitosis, and leaves the daughter cell capable of dividing again. The corresponding sort of cell division in prokaryotes is known as binary fission. In another type of cell division present only in eukaryotes, called meiosis, a cell is permanently transformed into a gamete and may not divide again until fertilization. Right before the parent cell splits, it undergoes DNA replication.

For simple unicellular organisms[nb 1] such as the amoeba, one cell division is equivalent to reproduction-- an entire new organism is created. On a larger scale, mitotic cell division can create progeny from multicellular organisms, such as plants that grow from cuttings. Cell division also enables sexually reproducing organisms to develop from the one-celled zygote, which itself was produced by cell division from gametes. And after growth, cell division allows for continual construction and repair of the organism.[2] A human being's body experiences about 10,000 trillion cell divisions in a lifetime.[3] Cell division has been modeled by finite subdivision rules. The primary concern of cell division is the maintenance of the original cell's genome. Before division can occur, the genomic information which is stored in chromosomes must be replicated, and the duplicated genome separated cleanly between cells. A great deal of cellular infrastructure is involved in keeping genomic information consistent between "generations" |

|