Biochemistry

Biochemistry, sometimes called biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes in living organisms, including, but not limited to, living matter. The laws of biochemistry govern all living organisms and living processes. By controlling information flow through biochemical signalling and the flow of chemical energy through metabolism, biochemical processes give rise to the complexity of life.

Much of biochemistry deals with the structures, functions and interactions of cellular components such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids and other biomolecules —although increasingly processes rather than individual molecules are the main focus. Among the vast number of different biomolecules, many are complex and large molecules (called biopolymers), which are composed of similar repeating subunits (called monomers). Each class of polymeric biomolecule has a different set of subunit types.[1] For example, a protein is a polymer whose subunits are selected from a set of 20 or more amino acids. Biochemistry studies the chemical properties of important biological molecules, like proteins, and in particular the chemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions.

The biochemistry of cell metabolism and the endocrine system has been extensively described. Other areas of biochemistry include the genetic code (DNA, RNA), protein synthesis, cell membrane transport and signal transduction.

Over the last 40 years biochemistry has become so successful at explaining living processes that now almost all areas of the life sciences from botany to medicine are engaged in biochemical research. Today the main focus of pure biochemistry is in understanding how biological molecules give rise to the processes that occur within living cells, which in turn relates greatly to the study and understanding of whole organisms.

Much of biochemistry deals with the structures, functions and interactions of cellular components such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids and other biomolecules —although increasingly processes rather than individual molecules are the main focus. Among the vast number of different biomolecules, many are complex and large molecules (called biopolymers), which are composed of similar repeating subunits (called monomers). Each class of polymeric biomolecule has a different set of subunit types.[1] For example, a protein is a polymer whose subunits are selected from a set of 20 or more amino acids. Biochemistry studies the chemical properties of important biological molecules, like proteins, and in particular the chemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions.

The biochemistry of cell metabolism and the endocrine system has been extensively described. Other areas of biochemistry include the genetic code (DNA, RNA), protein synthesis, cell membrane transport and signal transduction.

Over the last 40 years biochemistry has become so successful at explaining living processes that now almost all areas of the life sciences from botany to medicine are engaged in biochemical research. Today the main focus of pure biochemistry is in understanding how biological molecules give rise to the processes that occur within living cells, which in turn relates greatly to the study and understanding of whole organisms.

Enzyme Activity

Enzymes ( /ˈɛnzaɪmz/) are biological molecules that catalyze (i.e., increase the rates of) chemical reactions.[1][2] In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates sufficient for life. Since enzymes are selective for their substrates and speed up only a few reactions from among many possibilities, the set of enzymes made in a cell determines which metabolic pathways occur in that cell.

Like all catalysts, enzymes work by lowering the activation energy (Ea‡) for a reaction, thus dramatically increasing the rate of the reaction. As a result, products are formed faster and reactions reach their equilibrium state more rapidly. Most enzyme reaction rates are millions of times faster than those of comparable un-catalyzed reactions. As with all catalysts, enzymes are not consumed by the reactions they catalyze, nor do they alter the equilibrium of these reactions. However, enzymes do differ from most other catalysts in that they are highly specific for their substrates. Enzymes are known to catalyze about 4,000 biochemical reactions.[3] A few RNA molecules called ribozymes also catalyze reactions, with an important example being some parts of the ribosome.[4][5] Synthetic molecules called artificial enzymes also display enzyme-like catalysis.[6] Enzyme activity can be affected by other molecules. Inhibitors are molecules that decrease enzyme activity; activators are molecules that increase activity. Many drugs and poisons are enzyme inhibitors. Activity is also affected by temperature, pressure, chemical environment (e.g., pH), and the concentration of substrate. Some enzymes are used commercially, for example, in the synthesis of antibiotics. In addition, some household products use enzymes to speed up biochemical reactions (e.g., enzymes in biological washing powders break down protein or fat stains on clothes; enzymes in meat tenderizers break down proteins into smaller molecules, making the meat easier to chew). |

|

|

|

Basic Concept About Cellular Metabolism

Metabolism (from Greek: μεταβολή "metabolē", "change" or Greek: μεταβολισμός metabolismos, "outthrow") is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. The word metabolism can also refer to all chemical reactions that occur in living organisms, including digestion and the transport of substances into and between different cells, in which case the set of reactions within the cells is called intermediary metabolism or intermediate metabolism.

|

Locations Of Metabolic Pathways In Body

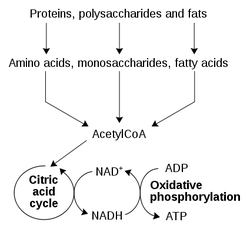

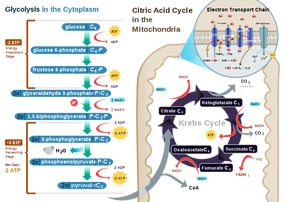

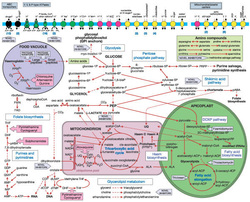

Carbohydrate catabolism is the breakdown of carbohydrates into smaller units. Carbohydrates are usually taken into cells once they have been digested into monosaccharides.[33] Once inside, the major route of breakdown is glycolysis, where sugars such as glucose and fructose are converted into pyruvate and some ATP is generated.[34] Pyruvate is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways, but the majority is converted to acetyl-CoA and fed into the citric acid cycle. Although some more ATP is generated in the citric acid cycle, the most important product is NADH, which is made from NAD+ as the acetyl-CoA is oxidized. This oxidation releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. In anaerobic conditions, glycolysis produces lactate, through the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase re-oxidizing NADH to NAD+ for re-use in glycolysis. An alternative route for glucose breakdown is the pentose phosphate pathway, which reduces the coenzyme NADPH and produces pentose sugars such as ribose, the sugar component of nucleic acids.

Fats are catabolised by hydrolysis to free fatty acids and glycerol. The glycerol enters glycolysis and the fatty acids are broken down by beta oxidation to release acetyl-CoA, which then is fed into the citric acid cycle. Fatty acids release more energy upon oxidation than carbohydrates because carbohydrates contain more oxygen in their structures. Amino acids are either used to synthesize proteins and other biomolecules, or oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of energy.[35] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase. The amino group is fed into the urea cycle, leaving a deaminated carbon skeleton in the form of a keto acid. Several of these keto acids are intermediates in the citric acid cycle, for example the deamination of glutamate forms α-ketoglutarate.[36] The glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis (discussed below). |

|

|

|

Cellular Respiration & Energy Generation

Cellular respiration is the set of the metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and then release waste products. [1] The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions, which break large molecules into smaller ones, releasing energy in the process as they break high-energy bonds. Respiration is one of the key ways a cell gains useful energy to fuel cellular activity.

Chemically, cellular respiration is considered an exothermic redox reaction. The overall reaction is broken into many smaller ones when it occurs in the body, most of which are redox reactions themselves. Although technically, cellular respiration is a combustion reaction, it clearly does not resemble one when it occurs in a living cell. This difference is because it occurs in many separate steps. While the overall reaction is a combustion, no single reaction that comprises it is a combustion reaction. Nutrients that are commonly used by animal and plant cells in respiration include sugar, amino acids and fatty acids, and a common oxidizing agent (electron acceptor) is molecular oxygen (O2). [[4589. The energy stored in ATP can then be used to drive processes requiring energy, including biosynthesis, locomotion or transportation of molecules across cell membranes. |

Overview Of Metabolism Processes

Metabolism (from Greek: μεταβολή "metabolē", "change" or Greek: μεταβολισμός metabolismos, "outthrow") is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. The word metabolism can also refer to all chemical reactions that occur in living organisms, including digestion and the transport of substances into and between different cells, in which case the set of reactions within the cells is called intermediary metabolism or intermediate metabolism.

Metabolism is usually divided into two categories. Catabolism breaks down organic matter, for example to harvest energy in cellular respiration. Anabolism uses energy to construct components of cells such as proteins and nucleic acids. The chemical reactions of metabolism are organized into metabolic pathways, in which one chemical is transformed through a series of steps into another chemical, by a sequence of enzymes. Enzymes are crucial to metabolism because they allow organisms to drive desirable reactions that require energy and will not occur by themselves, by coupling them to spontaneous reactions that release energy. As enzymes act as catalysts they allow these reactions to proceed quickly and efficiently. Enzymes also allow the regulation of metabolic pathways in response to changes in the cell's environment or signals from other cells. The metabolism of an organism determines which substances it will find nutritious and which it will find poisonous. For example, some prokaryotes use hydrogen sulfide as a nutrient, yet this gas is poisonous to animals.[1] The speed of metabolism, the metabolic rate, influences how much food an organism will require, and also affects how it is able to obtain that food. A striking feature of metabolism is the similarity of the basic metabolic pathways and components between even vastly different species.[2] For example, the set of carboxylic acids that are best known as the intermediates in the citric acid cycle are present in all known organisms, being found in species as diverse as the unicellular bacteria Escherichia coli and huge multicellular organisms like elephants.[3] These striking similarities in metabolic pathways are likely due to their early appearance in evolutionary history, and being retained because of their efficacy. |

|